In their recently released book, American Gun, Wall Street Journal reporters Cameron McWhirter and Zusha Elinson promise to tell The True Story of the AR-15. They only partially succeed in reaching that lofty goal.

A more accurate, though less marketable, title would be The AR-15: From Stoner to School Shootings. Over nearly 400 pages, the book thoroughly answers a question the authors pose in the Prologue (p. 6): “How did the weapon American soldiers carried in Vietnam become best known for killing schoolchildren?” But framing the book this way limits the truth the authors convey in the book.

They also fall short of what they claim American Gun does beyond the title. According to the book’s jacket, the authors “track the AR-15 from inception to ubiquity.”

“Writing with fairness and compassion, McWhirter and Elinson explore American gun culture, revealing the broad appeal of the AR-15, the awful havoc it wreaks, and the politics of trying to protect everyday people from mass shootings,” it says.

The authors are more successful in achieving their goal of explaining certain aspects of the AR (the politics) than others (broad appeal). But this is an important book that folks interested in the history, development, diffusion, misuse, and politics of the AR-15 will want to read beyond the book jacket, despite its limitations.

FROM INCEPTION TO UBIQUITY

McWhirter and Elinson conclude their Prologue by echoing the book’s subtitle: “This is the extraordinary story of the AR-15 rifle, the American gun” (p. 7). Extraordinary, indeed.

The book is divided into two parts. The 12 chapters in Part I cover the AR-15’s inception, giving insight into the life of designer Eugene Stoner as well as why and how he invented the rifle. It also covers the well-known problems the AR-15 ran into along the way from development to approval to deployment in the hands of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam.

As my knowledge of the AR-15’s history is largely limited to chapters on the rifle in Alexander Rose’s American Rifle (2009) and C.J. Chivers’s The Gun (2011), I am not well-equipped to assess the accuracy or novelty of this part of American Gun. I will leave it to firearms historians and gun cranks to make that assessment. I can say the writing here (and throughout the book) is captivating, with heroes and villains and a strong narrative through line. I was also impressed by the extensive interviewing, archival work, and source reading the authors put into their reporting.

Of course, I learned some things along the way. I now know that the AR in AR-15 doesn’t stand for assault rifle or automatic rifle (according to its critics) or even ArmaLite Rifle (according to its supporters). AR either stands for the first two letters in ArmaLite or for ArmaLite Research, depending on whether you believe Stoner’s collaborator Jim Sullivan or his daughter (p. 46).

I also learned that someone sabotaged the AR-15’s sights when it was being cold weather tested in Alaska (p. 77). George Sullivan was a shady businessman (p. 80). A little-known U.S. intelligence officer named William Godel saved the AR-15 by trying to get it into the hands of South Vietnamese soldiers in 1961 (pp. 91-107). Olin Mathieson’s ball powder propellant WC 846 was significantly inferior to DuPont’s extruded propellant IMR 4475 in the AR-15 (pp. 116-17). And so on.

The 20 chapters in Part II cover the AR-15’s ubiquity as it spread from its adoption as the U.S. military’s official M16 rifle and M4 carbine to a semi-automatic rifle sold in the commercial market to civilians.

At the risk of oversimplification, the basic narrative in Part II is that civilians did not want AR-15s at first because they didn’t look like proper rifles, but the 1994 assault weapon ban and clever marketing by a profit-hungry gun industry stoked ever more demand. Each step in the rifle’s diffusion into the civilian market was accompanied by violent crime and mass shootings which perversely fueled greater demand.

Here the authors don’t seem to care as much about establishing the ubiquity of the AR-15 in American gun culture (see point 4 below) as its ubiquity in the imagination of those Americans who associate it with school and other mass public shootings (see point 2 below). As they say near the book’s conclusion, “By the 2020s, Americans had adapted – sort of – to the unnatural reality that it was possible for a mass shooting to erupt at any time or any place” (p. 348).

“THE AWFUL HAVOC IT WREAKS”

For McWhirter and Elinson, the story of the AR-15 in American society centers on the relatively few but absolutely horrific instances of misuse. It doesn’t center on the tens of millions of AR-15s owned by millions of Americans who never make the news. Rather, the book answers a question the authors pose in the Prologue (p. 6): “How did the weapon American soldiers carried in Vietnam become best known for killing schoolchildren?”

They certainly answer this question well. The longer second part of the book focuses on the business of AR-15s, gun politics, and mass shootings; it unfolds roughly chronologically, beginning with the Colt AR-15 Sporter in 1963 and ending with the Buffalo-Uvalde-Highland Park mass shootings in 2022.

The accounts of mass shootings and their victims are compelling. My eyes welled up with tears reading the story of the Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre in Chapter 24, just as President Barack Obama’s did when he spoke that day from the White House (p. 274), just as any normal person’s would in thinking about the slaughter of 20 innocent elementary school children.

But as a scholar, I have to bracket emotions to assess the truth that the book promises. I see a number of moments at which the authors too easily glide from the rule to the exception. For example, they observe that “AR-15 marketing, from glossy magazine ads to video games, drew lots of new customers, and as targeted, many were young men. The vast majority INTENDED to be responsible gun owners, but the gun’s new image also attracted isolated and disturbed men. ONE OF THEM was a twenty-four-year-old graduate student in Denver” (p. 257, double emphasis added).

Note the casual slippage from the many to the one. In truth, the vast majority of the new customers were responsible gun owners, not isolated and disturbed men, much less spree killers.

Continuing on, the authors note, “After the Aurora massacre, no major federal legislation was proposed and many Americans moved on. But A FEW disturbed men, far from forgetting, obsessed over this massacre and others.” Of course, “ONE was . . . a thin, pale twenty-year-old who lived with his mother in Connecticut” (p. 266, double emphasis added).

The same pattern of movement from rule to exception is evident here. Most Americans who owned AR-15s moved on to the same non-newsworthy normality as before; they did not become disturbed men, much less a mass murderer of schoolchildren.

And herein lies the problem. As a proportion of AR-15s owned, or even as a proportion of homicides, deaths due to AR-15s are very exceptional.

I say this fully understanding a point my sister Rae made to me: They are not exceptional to those affected. As gun owners themselves frequently say, it’s not the odds, it’s the stakes. And certainly the trauma of mass shootings – as with gun violence generally – goes beyond the immediate victims. McWhirter and Elinson’s relentless elaboration of these ripple effects highlights how mass public shootings are often a form of terrorism – violent acts purposely designed to strike fear in a population beyond the immediate victims with the goal of achieving political or ideological aims. This makes them all the more frightening and much harder to stop.

But the sad truth is that mass murder has a long history in American society, predating the AR-15, as documented for the 20th century in Grant Duwe’s 2007 book, Mass Murder in the United States: A History.

McWhirter and Elinson themselves report FBI data showing “that AR-15s were used in only 24 of 250 active shooter incidents between 2000 and 2017” – just under 10% (p. 301). According to data they pull from the Violence Project, the use of AR-15s in mass public shootings where four or more are killed does seem to be increasing, from 5 out of 123 (4%) between 1996 and 2011 to 12 out of 40 (30%) from 2012 to 2018 (p. 322-23). But this still means that a large majority (70%) of mass public shootings did not involve AR-15s.

Where AR-15s have gotten the most attention is in the worst mass public shootings. AR-15s were used in 8 of the 11 worst mass public shootings in US history in terms of deaths, including two at elementary schools. This is why they are infamous for killing schoolchildren.

But the third and sixth worst mass shootings – at Virginia Tech in 2007 and Luby’s Cafeteria way back in 1991 – were executed with pistols, and the 1966 University of Texas tower bolt-action rifle mass shooting is still the top 10, for now. People with the serious intent to harm a large number of people, like those profiled by McWhirter and Elinson, may (probably will?) not be deterred by their inability to legally purchase an AR-15 and 30-round magazines.

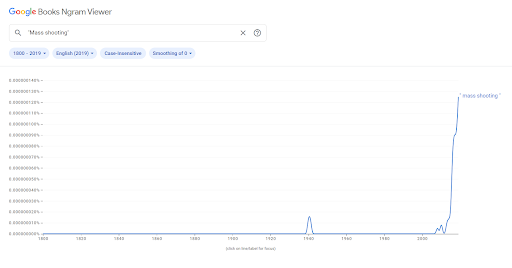

So, AR-15s are more commonly used in mass shootings now than in 1966 or 1991, but what else has changed since 2010 that gets short-shrift in American Gun? One important factor to consider is how these events get amplified by the media, whose coverage plays a key role in the culture of fear surrounding AR-15s and mass shootings. FiveThirtyEight highlighted this in a 2016 piece called “The Phrase ‘Mass Shooting’ Belongs to the 21st Century” which demonstrated that the increase in news reporting on mass shootings has far outstripped any increase in mass shootings themselves.

Inspired by FiveThirtyEight, I used Google’s Ngram Viewer to highlight how ubiquitous talk of “mass shootings” has become in published media during recent history.

The correlation between high-fatality mass public shootings with AR-15s and the increasing number of AR-15s in circulation should not obscure the role being played by old and new media (including the web).

Excessive news coverage may in fact inspire more and worse mass shootings, as the authors’ own reporting suggests. I understand it is impossible for McWhirter and Elinson not to name mass killers in their book. But back in 2017, I joined 146 other scholars in signing an open letter written by mass shooting expert Professor Adam Lankford asking the media “to take a principled stand in your future coverage of mass killers that could potentially save lives.” Among the requests: don’t use the name, image, or likeness of current or past perpetrators. The goal was “to stop giving fame-seeking mass shooters the personal attention they want.”

In addition to excessive old media news coverage, the proliferation of social media applications, the social web, high-speed internet, and smartphones certainly play a role in creating a pool of isolated and disturbed men from which a few become mass public shooters.

Focusing so much on the rifle itself does little to address these root causes. But what can be done?

THE “POLITICS OF TRYING TO PROTECT EVERYDAY PEOPLE FROM MASS SHOOTINGS”

No one is in favor of mass public shootings and everyone wants to protect everyday people from them. The challenge we face as a society is not on the ends but on the means.

Addressing the issue of mass shootings is made all the harder because guns in general have become a wedge issue in US politics. Even worse, “Half a century after Eugene Stoner invented the rifle, [the AR-15] had arrived as the fulcrum of America’s great gun divide” (p. 292). Invoking a perfect image, McWhirter and Elinson characterize the AR-15 politically as “just a cultural chew toy for angry partisans” (p. 305).

In treating the politics of AR-15s, the authors are balanced enough for me. We get the broad backdrop of our two-party system becoming ever more divided on the issue of guns, with Democrats embracing gun control more and more from 1968 onward, and the NRA embracing Republicans more and more from 1977 onward. We more specifically see Dianne Feinstein stubbornly clinging to her ill-fated assault weapon ban idea well into the 21st century (and some of her pettiness around that, p. 234), and Wayne LaPierre bitterly clinging to ill-founded ideas about what motivates mass killers and a slogan about “good guys with guns” that I dislike quite a bit.

Despite the fact that Beto O’Rourke’s rallying cry “Hell yes, we’re going to take your AR-15” was codified in the Democratic Party’s 2020 platform (p. 328), McWhirter and Elinson actually suggest the best approaches to addressing mass public shootings may not target the AR-15 itself.

Although not every mass public shooting can be prevented, it is impossible for me to read about Parkland (p. 324) or the Nashville Waffle House (p. 325) or Buffalo (p. 352) or Highland Park (p. 359) and not think they were all preventable. Without even engaging in the culture war over guns, we could make a relatively rare occurrence even rarer through preventative measures like better mental health care services and well-drafted red flag laws. One problem is that all of the major “gun violence prevention” (née gun control) groups that advocate for policies like these also advocate for assault weapon bans, including Brady, Everytown, and Giffords. This draws these policies into the broader culture war.

McWhirter and Elinson rightly identify that we Americans are fighting a “culture war over the AR-15” (p. 298). In another very astute passage, they write that by the year 2020, “The image of the AR-15 had become a political and cultural symbol infused with meaning far beyond the gun debate. . . . To scorn it meant you were a Democrat and a liberal who backed stricter gun control laws. To embrace it meant you were pro-gun, conservative, likely pro-Trump. It became a tribal emblem, immediately signaling where you stood on the American political spectrum” (p. 333).

These are familiar dynamics of culture wars, but they hide the reality that most people – even if they are not conscientious objectors to the culture war over guns like I am – do not actively engage in these cultural conflicts.

Although the authors claim the culture war has “spilled from the halls of Congress, to kitchen tables, to Facebook, and into the local coffee shop” (p. 298), this passage is actually somewhat misleading. The kitchen table in question belonged to someone who became an unintentional activist on Facebook and the local coffee shop was targeted by an open-carry activist. But these individuals are exceptional. As in most culture wars, the vast majority of Americans are not active combatants. Most owners of AR-15s are not out fighting a culture war on their behalf. That makes them less newsworthy, of course. But a true history of the AR-15 should do more to incorporate their experiences and voices than McWhirter and Elinson do in American Gun.

“EXPLORE AMERICAN GUN CULTURE” TO EXPLAIN “THE BROAD APPEAL OF THE AR-15”

Gun companies are certainly part of gun culture, as are gun politics. But can you tell The True Story of the AR-15 without attempting to understand some of the 10+ million Americans who own “semiautomatic military-style rifles”, the vast majority of whom are not profit-hungry business executives, shady salesmen, criminals, mass murderers, insurrectionists, politicians, or political activists?

This is the fundamental inequity of the book from my perspective. The promised “ubiquity” I was hoping for was the widespread civilian ownership of AR-15s by normal people. The ubiquity I got was mass shootings. To wit: We learn more about one victim – the entire concluding 17-page Chapter 32 focuses on San Bernardino shooting survivor Valery Kallis-Weber – than about all non-deviant AR-15 owners combined. This is not to say Kallis-Weber doesn’t deserve that much consideration. Her story is painful and compelling. But there is no counterbalancing chapter that paints a compelling picture of why average gun owners own AR-15s. I’m not even saying a single 17-page chapter on a single AR-15 owner, but one chapter for the 4.2% of the entire U.S. adult population who own these kinds of rifles (according to researchers at Harvard and Northeastern Universities).

The two chapters of the book that do focus primarily on AR-15 owners are linked by their charged titles, “Molon Labe” (Chapter 25) and “Come and Take It Nation” (Chapter 29).

In Chapter 25, we meet Chris Waltz who started the Facebook group “AR-15 Gun Owners of America” after Sandy Hook when the possibility of an assault weapon ban seemed quite real. Waltz tells the authors, “I didn’t understand how you could blame a whole society for the actions of one madman, and then penalize the whole society for that, when you had people who day in and day out, millions of people, who used it responsibly” (p. 287). An eminently sensible position for an AR-15 owner to take. Of course, we come to learn that Waltz embraced the Three Percenter movement (p. 290) and that “vocal and angry AR owners led the gun-rights agenda. No compromise” (p. 293). Waltz’s story then smoothly transitions to that of C.J. Grisham as embodying the intersection of “Molon Labe” and the AR-15 (p. 296). “Throughout the summer of 2013,” readers will recall, “Grisham and supporters armed with AR-15s showed up in coffee shops, restaurants, grocery stores, and department stores” (p. 297).

Chapter 29 begins in the same vein as Chapter 25 leaves off: “a doughy sixty-three-year-old man wearing a pink Brooks Brothers polo shirt and khakis emerged from his mansion built to look like an Italian palazzo. The man looked out over a tall hedge and cradled a Colt AR-15” (p. 332). Mark McCloskey was guarding his St. Louis home against demonstrators protesting the murder of George Floyd who were marching through his neighborhood. Although many of my AR-15-owning friends and I found the event cringeworthy, for McWhirter and Elinson, “the surreal incident underscored the fact that America had entered a tumultuous era in which the AR-15 was everywhere” (pp. 332-33). It was ubiquitous.

But the ubiquity of AR-15s is not conveyed with the promised fairness and compassion. In addition to McCloskey, in this single chapter we also find the AR-15 in the hands of Kyle Rittenhouse (p. 334), a white nationalist group called “the Base” (p. 335), the Boogaloo Bois (p. 336), extremists building ghost guns (p. 336), MAGA supporters with AR-15 Confederate battle flags (p. 337), and Oath Keepers (p. 338).

And one potentially unproblematic gun owner: Taylor Winston.

Winston became known for his heroic actions in the immediate aftermath of the Las Vegas mass shooting. A Marine Corps veteran, he purchased an AR-15 for the first time in the wake of the attack because it made him feel safe. McWhirter and Elinson build on Winston’s story by reporting that Americans owned more than 20 million AR-15s by the end of 2021. But immediately following this striking data, we are back at the protests and riots of summer 2020 during which “self-appointed sentinels claiming they were working to restore order armed themselves with AR-15s” (p. 334).

In this chapter, we do get a lone paragraph on a rally at the state capitol in Virginia that drew over 20,000 attendees, some carrying AR-15s (p. 336). Although McWhirter and Elinson don’t characterize the attendees or the event, the Associated Press reported that the rally was peaceful and “the mood was largely festive.” Of course, in American Gun, this uneventful, peaceful, and festive gathering of gun owners is bookended by a paragraph about the Base and how they “trained with AR-15s” (p. 335) and a paragraph about “the Boogaloo Bois, antigovernment extremists . . . carrying AR-15s” (p. 336).

These are the faces of AR-15 owners for McWhirter and Elinson. To be perfectly clear, I am not challenging the veracity of what they include but questioning the huge swaths of the reality of AR-15 ownership that they exclude. Because AR-15s are ubiquitous.

According to the Harvard/Northeastern 2019 National Firearms Survey, over 23 million “semi-automatic military-style rifles” are owned (almost 7% of all guns) by nearly 11 million U.S. adults (over 4% of the entire adult population). The vast majority of these fall under McWhirter and Elinson’s AR-15 label. These figures should also be treated as minimum estimates because they not only precede the Great Gun Buying Spree of 2020+, but we also know that many respondents do not admit to surveyors that they own firearms, much less ones potentially subject to bans. These researchers also separately count ownership of “semi-automatic hunting rifles,” some unknown portion of which are likely also AR-15s.

From among these millions of U.S. adults, McWhirter and Elinson couldn’t find a few normal people to hang around with or a dozen or two normal people to interview? Where is someone like Jon Stokes, for example, a computer engineer who has two master’s degrees from Harvard Divinity School, co-founded Ars Technica, was an editor at Wired, and continues to be a progressive gun nut. He has written thoughtfully on “Why I ‘need’ an AR-15.”

Or they could have lived up to one of the promises of the book, to “explore American gun culture, revealing the broad appeal of the AR-15” by joining my Sociology of Guns seminar at Wake Forest University for our field trip to the gun range during which we unproblematically shoot, among other guns, an AR-15. Or they could have attended any number of shooting events and observed the normal core of AR-15 owners firsthand doing normal things with their rifles.

But doing so would have disrupted the coherence of their narrative. A narrative that runs only from Stoner to school shootings and, unfortunately, leaves out all the rest.

Only Members can view comments. Become a member today to join the conversation.