The United States Supreme Court decision in NYSRPA v. Bruen was not surprising to many, but neither was the response by those opposed to it.

Of note are comments by New York Governor Kathy Hochul (D.) about how “the insanity of the gun culture that has now possessed everyone all the way up to even to the Supreme Court.” She called the decision “absolutely shocking” and “frightful in its scope,” which “could place millions of New Yorkers in harm’s way.”

Here Hochul connects the expansion of lawful gun carry with increases in accidental or intentional gun injury. In doing so, she is taking a side in a political debate over whether civilian gun carrying is a net positive or negative for society that is as old as gun carry laws themselves.

Since the concealed carry revolution of the late 20th century, this has become an empirical question. John Lott’s book, More Guns, Less Crime, is a touchstone in an ongoing back-and-forth among scholars with no resolution in sight.

Much of this academic debate takes place over my head statistically, but when new studies are published on the topic, I do try to understand the empirical basis for their claims. That’s why I want to discuss two such recent studies: “Analysis of ‘Stand Your Ground’ Self-defense Laws and Statewide Rates of Homicides and Firearm Suicides” by Michelle Degli Esposti, et al. and “Officer-Involved Shootings and Concealed Carry Weapons Permitting Laws: Analysis of Gun Violence Archive Data, 2014–2020” by Mitchell L. Doucette, et al.

Both of these studies examine the effect of liberalized gun carry laws on adverse societal outcomes. The first study finds that passage of “Stand Your Ground” (SYG) laws are associated with increases in homicide rates, and the second study finds that passage of “permitless carry” laws are associated with increases in officer-involved shootings (OIS). We can certainly debate whether all officer-involved shootings represent a negative outcome in and of themselves. Still, I am willing to accept the authors’ assertion here that they are examining “the negative health consequences [of] Permitless CCW laws” (SIC) to focus on this other issue.

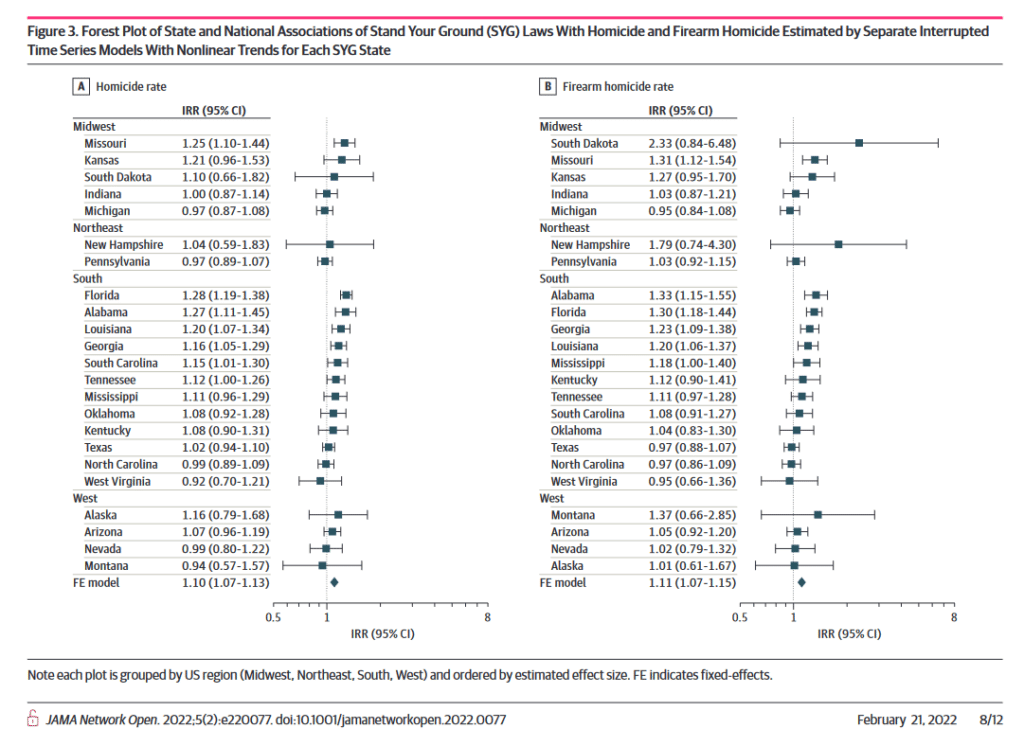

Examining the difference between 23 states that enacted SYG laws from 2000-2016 and 18 states that did not, Esposti and colleagues conclude: “the enactment of SYG laws was associated with an abrupt and sustained eight percent to 11 percent national increase in monthly homicide and firearm homicide rates.”

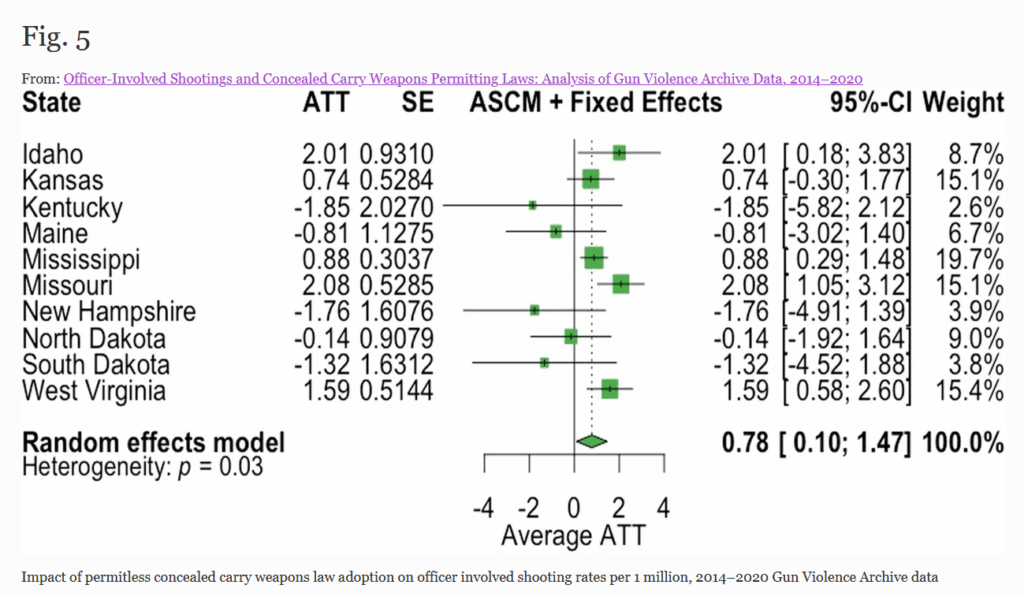

Examining the difference between ten states that adopted permitless carry laws from 2015-2019 and various synthetic control states, Doucette and colleagues conclude: “Permitless CCW adopting states saw a 12.9 percent increase in the OIS victimization rate or an additional four OIS victimizations per year, compared to what would have happened had law adoption not occurred.” I should note that synthetic control methods are complex and imperfect and readers who are able to do so may wish to interrogate these authors’ methodology which is extensively documented.

But, accepting the studies as they have been presented, what happens when we look below the surface of these summary statistics?

I have previously argued that the problem with averages is they can obscure significant underlying differences in the data producing the averages. Two very different distributions of data can result in the same average. For example, imagine two states that pass a liberalized gun carry law and both experience a ten percent increase in homicides. The average increase is ten percent Now imagine two other states that pass the same law, but this time one sees a 30 percent increase in homicide and one sees a ten percent decrease. The average increase is again ten percent. The average as a summary statistic only tells part of the story.

When we look at the underlying data in both these studies, we see the problem with averages.

Recall that the Esposti team found that collectively the 23 states with SYG laws saw eight to 11 percent increases in monthly rates of homicide. Looking at the underlying data tells a different story, though. Some states, notably in the South, saw significant increases in homicides while even more states, including many in the South, saw no increase.

The Esposti team finds that Stand Your Ground laws correlate to more firearms homicides nationally, but of 23 states with SYG laws, only five saw “incident rate ratios” large enough to reject a null hypothesis of “no effect”: Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Missouri.

Even ignoring the “association is not causation” argument, if a theorized casual factor only has an effect in 22 percent of cases, it would not seem to be an independent causal factor in the outcome of interest. We need to know much more about what else is going on in those five states that act in concert with the gun policy that is not happening in the other 18 states with the same policy.

What about the Doucette study that purports to show that the shift from shall-issue to permitless carry laws is associated with a 12.9 percent increase in the number of officer-involved shootings of civilians?

Of ten permitless carry states that fit their selection criteria, only four had increases in officer-involved shootings large enough to be considered greater than chance: Idaho, Mississippi, Missouri, and West Virginia. Only two of the ten states (Mississippi and Missouri) show this effect across all four synthetic control models tested.

Bottom line: In only 20 to 40 percent of the states examined by Doucette’s team was the theorized causal factor a significant predictor of officer-involved shootings. This means the modal state did not follow this pattern.

It’s worth noting that, as with the Esposti study, Doucette’s team found Missouri to be one of the states in which a liberalized carry law was associated with a negative outcome. Perhaps there is something unique about Missouri (either in and of itself or in conjunction with liberalized gun laws) that makes it such an outlier relative to the “average” American state?

I don’t believe the data in these two studies show what the authors want them to show about the negative effects of liberalized gun carry laws. However, it’s important to note they don’t show the opposite either: that liberalized gun carry laws have a net positive effect.

The empirical question first raised by John Lott remains to be answered definitively.